My current book project, Raw Materiality: Making Sugarcane into Sustainable Futures, focuses on the production of sugarcane-based biofuels and bioplastics in Brazil.

What would fuels, plastic, synthetic fabric, and even toothpaste be made of if we stopped using petrochemicals? Some scientists in Brazil have an answer: sugarcane.

Amid fossil-fuel-driven climate change and intensifying consumption from development, finding sustainable replacements for petroleum-based fuels has been a pressing concern for decades. Recent scientific advances have offered plant-based products as a solution. These could replace the wide variety of petrochemicals used daily, from fuel to plastic to synthetic fabrics.

However, given histories of plantation-based colonialism, scientists in places like Brazil contend that such plant-based solutions to climate change will not be one-size-fits-all.

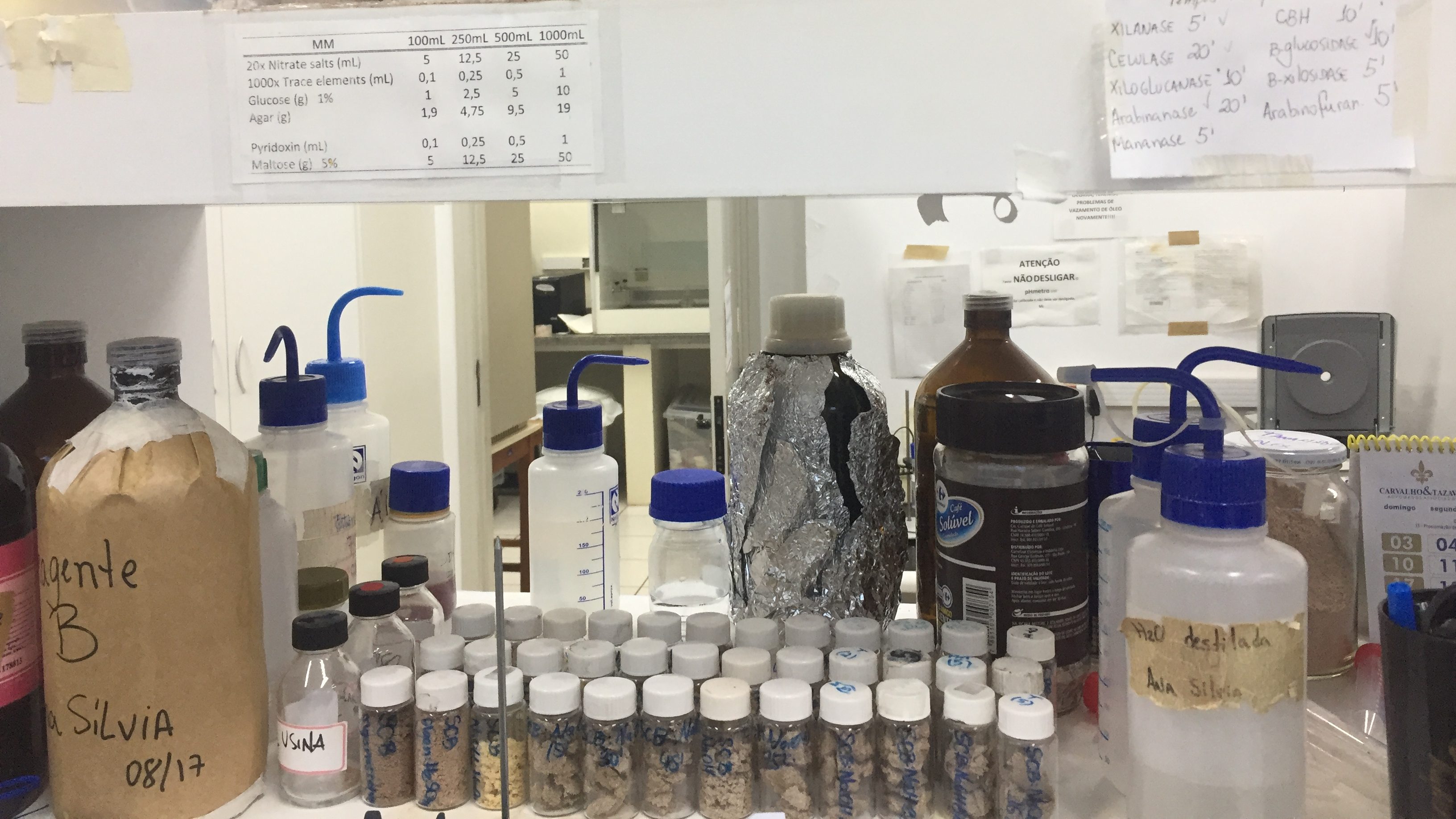

My research studies how scientists make bioproducts from sugarcane in Brazil in the present day. If between the 16th and 20th centuries Brazilian sugarcane was located at the nexus of plantation and factory, in the 21st century it is located at the nexus of industrial-agricultural field, flexible factory, and biotech laboratory. Building on the extensive Brazilian scholarship on contemporary sugarcane labor, my research looks at a different, increasingly important site of sugarcane production: the production of knowledge in the lab. I ask how scientists transform this crop with a long, violent history into biofuels, bioplastics, and beyond.

Drawing on ethnographic methods—including participant observation and interviews—and a methodological technique I call a sugar library, my research spells out how technical practices of transforming molecules in the lab shape broader social ideas of transforming society.

This research has been supported by a NSF Dissertation Improvement Grant (BCS-1918156) and the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (1842494).

All photographs on this page by Katie Ulrich, with the exception of the last one, taken by a sugarcane genetics researcher.