Sugar, particularly that from sugarcane, takes many different shapes and forms in the world. During my research on sugarcane biofuels and bioplastics in Brazil, the largest producer of the crop, I started tracking in a spreadsheet all the various forms of sugar or sugarcane I encountered in my fieldwork. I called this my sugar library.

I’ve since explored making the sugar library, which contains hundreds of artifacts, available as an open online repository that other researchers can access and use.

The sugar library is meant to be interesting or helpful to other social scientists or humanities researchers investigating myriad topics from sugarcane to resource extraction to agriculture to commodities to biotech. As a teaching tool, it can guide students in understanding the multiplicity of meanings and material forms that something like sugarcane, a seemingly basic commodity crop, takes in the world. It models the gathering of artifacts that one might have never thought to find in relation to an object like sugarcane, bringing them into the scope of analysis when they previously remained on the periphery. Certain artifacts and juxtapositions of items in the library may generatively unsettle one’s inherited conceptual frameworks about sugarcane, science, and sustainability.

The sugar library is also an experiment with sharing ethnographic data in some other form than polished journal articles or books. Accordingly, the sugar library is contingent and enacts situated knowledge. This approach doesn’t assume that completeness yields the best chance at understanding the phenomena we study, nor that completeness is even possible. The sugar library has little of what one perhaps might expect to find in a library of artifacts about sugarcane in Brazil—entries relating to deforestation, or the labor of cultivating and harvesting cane, or its histories of slavery, racialized violence, and Black and Indigenous resistance. Instead, the library gathers items that are harder to anticipate, like the dozens of different kinds of cane that were meaningful to people, from touristy cane to theoretical cane; “living museums” of cane; and the wide range of other scientific research projects done in the name of sugarcane biofuels. Silences within archives are productive. The tension between the library’s relative lack of entries about those aspects of sugarcane’s social lives one might expect and its surfacing of other items made hard to imagine is the productive engine for examining the social and political impacts of Brazilian sugarcane-based bioproducts today.

I write about the development of the sugar library in this blog post on Platypus: The CASTAC Blog.

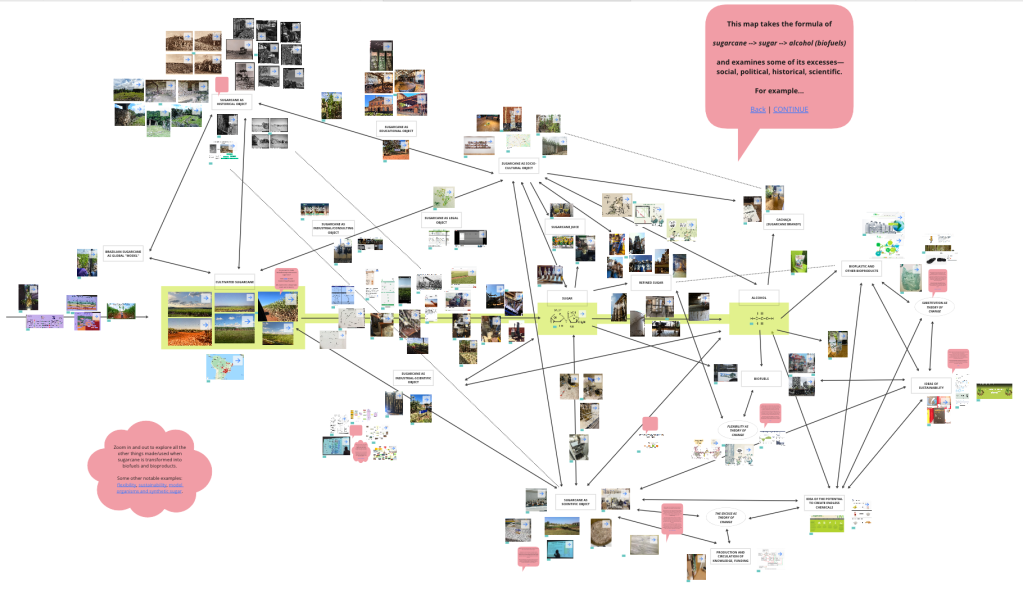

An earlier experiment with the sugar library, called Click to Transform Sugarcane, sought to share and visualize some of the sugar library artifacts through interactive mapping. It was developed through conversations with the Ethnography Studio and EMERGE project.

Click the image below to explore it on Miro.